Spotlight on…. Canine Transmissible Cancer

Infectious Canine Cancer

The percentage of canine cancer patients has grown exponentially in the last few decades, so much so that an Animal Cancer Registry was established in 1985. Research has established that 45% of dogs over the age of 10 are dying of cancer and an estimated 1 in 3 have the potential to develop it, with a prevalence in certain breeds, the highest risk being in:

- Boxer

- Golden Retriever (60% of breed mortality)

- Rottweiller

- Bernese Mountain Dog

The risks are higher in female than male dogs due to mammary cancer accounting for 70% of all incidences (Merlo et al. 2008), and three to four times higher in spayed and neutered pets (Torres et la Riva et al. 2013).

Whilst many holistic owners believe that this is due to the combination of commercial food products, vaccines and other chemicals that our pets are exposed to, there has been recent media coverage of a transmissible cancer, which is scarier still.

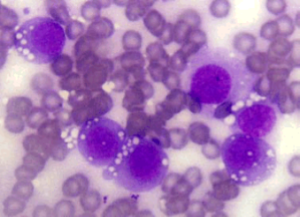

Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumour (CTVT) is a unicellular pathogen, where the infectious agent is the cancerous cell itself. Microsatellite analysis indicates this tumour is over 6,000 years old and originated back when dogs were first domesticated.

Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumour (CTVT) is a unicellular pathogen, where the infectious agent is the cancerous cell itself. Microsatellite analysis indicates this tumour is over 6,000 years old and originated back when dogs were first domesticated.

The vector is sexual, cells reproduce on the new host over a period of two to six months to form a tumour-like growth usually around the genitalia.

Without treatment these tumours usually regress due to the hosts natural immune response (Siddle & Kaufman, 2014) after one to three months and with complete regression comes complete immunity (Rebbeck et al. 2009).

CTVT is one of only two known communicable cancers and the oldest cancer in the natural world (Lakody, 2014). DNA analysis shows that CTVT first occurred in a dog with “low genetic hetrozygosity” (i.e. that was highly inbred) 11,000 years ago, therefore it was initiated due to human selective breeding (Murchison et al. 2014).

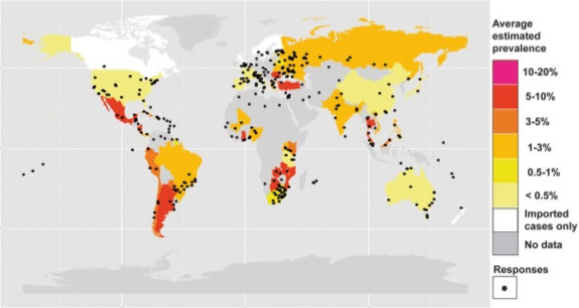

CTVT is prevalent in at least 90 countries and all inhabited continents, and is estimated to have infected at least one percent or more of dogs in at least 13 countries in South and Central America, as well as at least 11 countries in Africa and 8 in Asia.

In the USA and Australia it has only been reported in remote indigenous communities and prevalence has declined in Northern Europe. This disease is mostly prevalent in areas with free roaming canines and has disappeared from the UK (Strakova, 2014).

Surgical removal of tumours has been shown to leave a 30% reoccurrence rate, however this was only studied in 10 dogs, the same study found no recurrence in 10 dogs given chemotherapy, but these dogs were only followed for six months (Awan et al. 2014). CTVT tumours are generally not fatal as the hosts’ immune response controls or clears the tumours after transmission and a period of growth (Siddle & Kaufman, 2014), however metastasis does occur in immune-suppressed animals. The most immediately effective allopathic therapy has been reported to be ‘Vincristine’ (VCR) also used as an immunosuppressant, with known side effects of:

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Low White Blood Cell Count

- Bladder Irritation (Canine Cancer Library, 2014)

- Chemical burns on skin contact

Therefore if a strong immune system, developed from a natural balanced diet, preferably through generations of dogs, as Epigenetics have been shown to be a contraction factor (Siddle & Kaufman, 2013) can destroy these tumours and render the host non-susceptible to reinfection, is the recommended protocol of surgery and chemotherapy (Awan et al. 2014) simply not worth the risk of metastasis, (as one single cell left on an immune compromised animal could lead to this) and further damage that these leave particularly for natural rearers, and future genetics, dependent of course on the severity of the tumour?

Therefore if a strong immune system, developed from a natural balanced diet, preferably through generations of dogs, as Epigenetics have been shown to be a contraction factor (Siddle & Kaufman, 2013) can destroy these tumours and render the host non-susceptible to reinfection, is the recommended protocol of surgery and chemotherapy (Awan et al. 2014) simply not worth the risk of metastasis, (as one single cell left on an immune compromised animal could lead to this) and further damage that these leave particularly for natural rearers, and future genetics, dependent of course on the severity of the tumour?

N.B. For further details on the risks of spaying and neutering please see Turner, H. (2014) “The Spay/Neuter Health Denigration” Healthful Dog 1[2]:52-53

References:

Awan, F. Ali, M.M. Ijaz, M. & Khan, S. (2014) Comparison of Different Therapeutic Protocols in the Management of Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumour: Review of 30 Cases. Global Veterinaria. 12[4]:499-503

Canine Cancer Library (2014) Common Chemotherapy Side Effects. Available from: http://www.wearethecure.org/chemotherapy-side-effects (Accessed 16/11/2014)

Lokody, I. (2014) The Origin and Evolution of an Ancient Cancer. Cancer Genetics. 14:152

Merlo, D.F. Rossi, L. Pelligrino, C. Ceppi, M. Cardellino, U. Capurro, C. Ratto, A. Sambucco, P.L. Sestito, V. Tanara, G. & Bocchini, V. (2008) Cancer incidence in pet dogs: findings of the Animal Tumor Registry of Genoa, Italy. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 22[4]:976-984

Murchison. E.P. Wedge, D.C. Alexandrov, L.B. Fu, B. Martincorena, I. Ning, Z. Tubio, J.M.C. Werner, E.I. Allen, J. De Nardi, A.B. Donelan, E.M. Marino, G. Fassati, A. Campbell, P.J. Yang, F. Burt, A. Weiss, R.A. & Stratton, M.R. (2014) Transmissible Dog Cancer Genome reveals the Origin and History of an Ancient Cell Lineage. Science. 343:437-440

Rebbeck, C.A. Thomas, R. Breen, M. Leroi, A.M. & Burt, A. (2009) Origins and Evolution of a Transmissible Cancer. Evolution. 63[9]:2340-2349

Siddle, H.V. & Kaufman, J. (2013) A tale of two tumours: Comparison of the immune escape strategies of contagious cancers. Molecular Immunology 55[2]:190-193

Siddle, H.V. & Kaufman, J. (2014) Immunology of Naturally Transmissible Tumours. Immunology. DOI: 10.1111/imm.12377

Strakova, A. & Murchison, E.P. (2014) The Changing Global Distribution and Prevalence of Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumour. BMC Veterinary Research. 10:168

Torres de la Riva, G. Hart, B.L. Farver, T.B. Oberbauer, A.M. Locksley, L. McV. Messam, N.W. & Hart, L.A. (2013) Neutering Dogs: Effects on Joint Disorders and Cancers in Golden Retrievers. PLOS DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055937